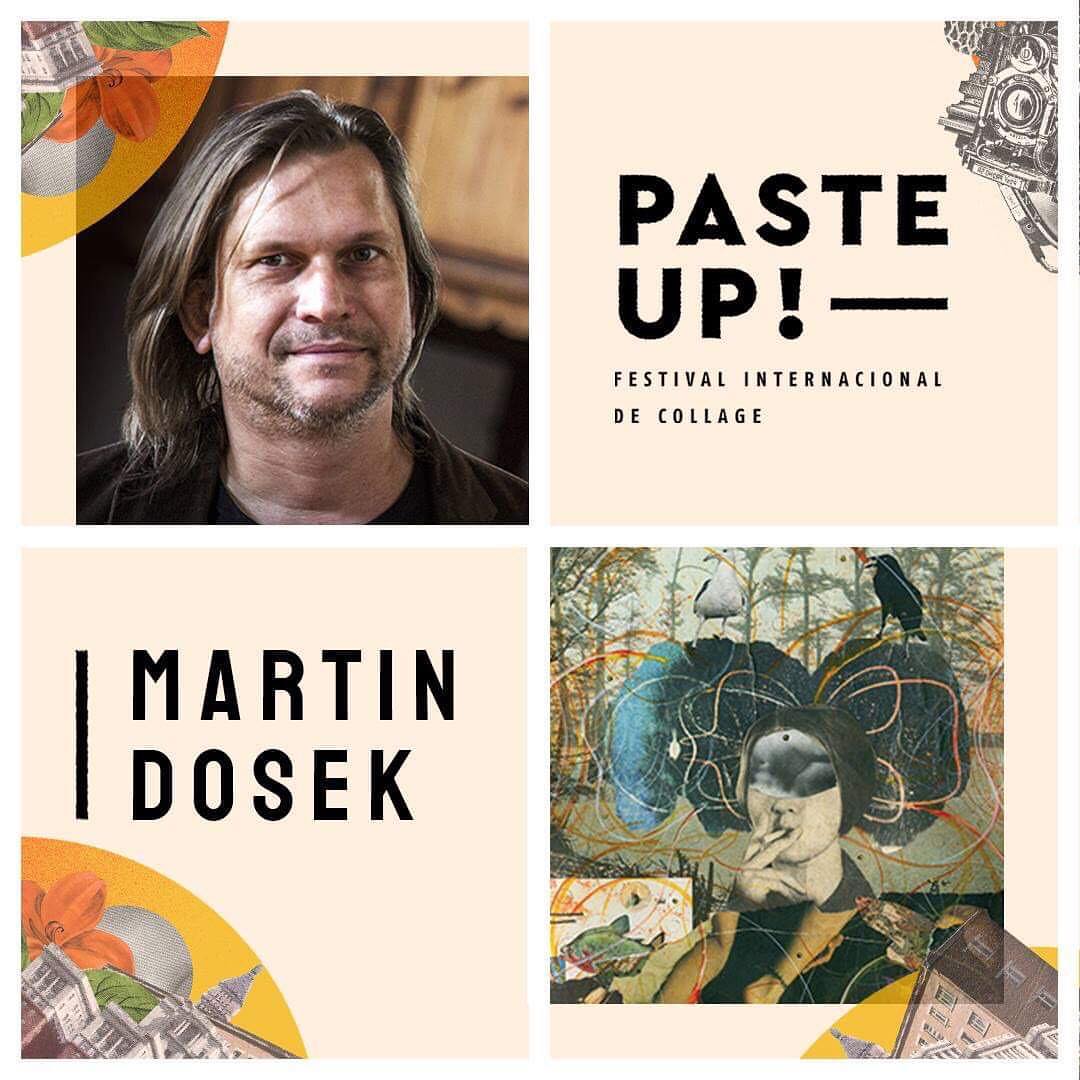

Biografie

Martin Došek

born 8. 4. 1967

in Pardubice

Own work is concerned with the age of 20 years , his collages regular exhibitions since 1993. Since 1998 he works as creative director in the agency MAXX Creative.

Collage is a Surrealist Idea and Process

Even after a hundred years of its existence, there is still something captivating about fragments of reality that acquire a new environment and context. At the same time, in both flat collages and spatial assemblages, there is a Pop Art sensitivity to the human being in the midst of the metropolis. Collage utilizes various printed sources with which our civilization floods itself. There is also the idea of recycling—or perhaps upcycling.

A reintroduction of something forgotten onto the scene of today. While the original purpose of printed papers was entirely banal, embarrassingly topical, and quickly forgotten, thanks to Došek’s imagination, scissors, and glue, individual elements take on a new and fascinating meaning. Collage is somewhat of a dream, a story from another dimension, perhaps an oracle, but above all, a great creative freedom.

Collage fulfills its purpose by compelling us to speculate about its meaning. Within the small space of a collage, the author can play with an engaging network of interrelated and ever-changing connections. This artistic technique initiates a process of questioning and continuous doubt within us. The ways of reading it are varied, and it is difficult to say that there is only one correct interpretation.

Collage began appearing on humorous postcards and in satirical magazines even before the end of the 19th century. It was not considered avant-garde art until around 1910, roughly at the same time when the world was astonished by abstract painting, and science was slowly coming to terms with Einstein’s special theory of relativity. Cubist artists experimented with collage, but it was the Surrealists who truly established it. Max Ernst’s collages, made from 19th-century xylographic novels filled with erotica, monsters, and strange stories, fit into an era when Kafka’s Metamorphosis could already be read.

The chance encounters and the creation of new realities fascinated the poets of the Devětsil group, with Karel Teige and Adolf Hoffmeister working with collage. Ladislav Novák, Adriena Šimotová, and, of course, the master of collage, Jiří Kolář, followed suit. Teige first encountered collage as the editor of a school magazine Kniha všeho at the Reálné Gymnázium in Křemencova Street, though he did not publish his own collages until 1951.

Even though collage is an individual statement, it works with universals—human figures, objects, and familiar environments derived from posters, television, and magazines, from which Martin Došek cuts his pieces. For a collagist, building a personal archive plays a crucial role. How deeply they delve into past source materials, or how broadly they sift through themes from magazines, catalogs, and flyers, all influences their work.

Through collage, Martin Došek tells stories. Storytelling is a major theme of our time. By seeking stories within the fragments of messages that surround us, we gain a better understanding of the world and human society. The figure of the storyteller, scooping up characters and events from a cauldron of memories, dreams, and visions, has always been fundamental to our culture—from shamans, whom our ancestors listened to, through medieval wandering bards, Enlightenment collectors of legends and fairy tales, to Tolkien, Hollywood films, and modern advertising campaigns. However, in the case of collage, we construct our own stories; the artist provides hints, but the interpretation is ours to make. Collage teaches us to read clues, often very subtle ones. A collage exhibition, therefore, might resemble a training session in visual literacy.

As we view collages, we become aware of what time has carried away. Collage is deeply personal yet aspires to be a mirror of society. At its core, it is an exploration of printed visual material, which is inherently sociological. It is a kind of post-production—collage gathers and confronts pre-existing images, reworking and manipulating them, placing them into unusual contexts and foreign settings. Surrealism defined this process as an identity theft, replacing one identity with another.

Collage is often perceived as the domain of poets—Vítězslav Nezval, Jiří Kolář, and Ivan Wernisch were adept at cutting and assembling. It works with images on a level of intangible imagination, in ways not entirely possible in traditional painting. In collage, chance and intentionality merge in ever-changing proportions. Surgical cuts and torn edges, reminiscent of peeling posters, require a tactile engagement with materials and lead to expressive articulation. We sense the influence of cinematic vision, and we know that art therapists use collage as a projective material. Everyone can find something personal in it.

It is like opening secret drawers. What most people discard, burn, store away, or forget after reading, Martin Došek finds pearls within. In unusual juxtapositions, he elevates mundane elements onto a brightly lit stage—whether on the electronic display of a computer, laptop, tablet, or smartphone. He digitizes and uploads his collages to social media immediately after their creation. Long before they are exhibited in a gallery, they vibrate and ping in our pockets or on our desks while we work. Došek consciously plays with both the physical and immaterial nature of his collages. Given how frequently his new collages appear in the virtual space, one could almost call it “Not a day without a collage”.

Martin Došek’s work has long surpassed the definition of a hobby, ascribed to it by the artist himself, and has become a way of life. In dimensions corresponding to the original sources—magazines and newspapers, designed to be held in hand or placed on a table—new stories emerge in the evening or weekend hours. These narratives reveal unusual relationships, intertwining temporal planes and layers of meaning.

The heroines of Došek’s stories are often women, partly because their images were predominantly featured in past printed media. It is interesting to note that an almost complete exclusion of the male element is also evident in the collages of Karel Teige. Female figures, or occasionally young boys, are the protagonists, but it is unclear whether they hold the role of object or subject.

A recurring motif is water—submersion, glimpses beneath the surface—evoking a journey between consciousness and the subconscious. Eyes, boats, birds, and sometimes a cat appear frequently. The artist confronts us with classical sculptures (Michelangelo’s David), which, in these dreamlike scenes, serve as our ancient archetypes. Citations of famous artworks play a crucial role. A guiding compass is the woman—the odalisque from Ingres’ painting (The Eyes of the Ocean). His storytelling leads us through different settings at various times of day—bright daylight, dusk, dawn—and immerses us in mysterious nocturnal scenes.

Došek sometimes enhances his collages with drawings (A Thousand Kisses, Butterflies), suggesting movement through horizontal cuts. Tiny clippings are scattered across the surface (Half-Life). As a metaphor, he chooses the world of plants (Hummingbirds, The World of a Surrealist Painter), and he constructs Lost Cities for both himself and us. He playfully manipulates anatomical elements, revealing beating hearts outside the body.

Beyond traditional cut-and-paste techniques, Martin Došek embraces modern technologies, from Photoshop to AI. The intrusion motif that he once playfully applied to masterpieces of art history has expanded thanks to artificial intelligence. Instead of merely inserting a face, he integrates entire figures—standing beside Botticelli’s Venus with a ridiculous inflatable ring, embracing Mona Lisa as if he were her unseen husband, or peeking under the skirts of rococo ladies. AI also allows for the enlargement of his originally small collages. Yet, the path always leads deeper into mystery.

About the Artist

Martin Došek was born in Pardubice in 1967. He has been engaged in his own artistic practice since his twenties. He has been exhibiting collages regularly since 1993 and participates in international collage showcases worldwide, where he has received numerous awards. He collaborates with selected international artists through collage exchanges and illustrates books for friends. Since 1998, he has been the creative director of MAXX Creative agency.

Martina Vítková, July 2024

---

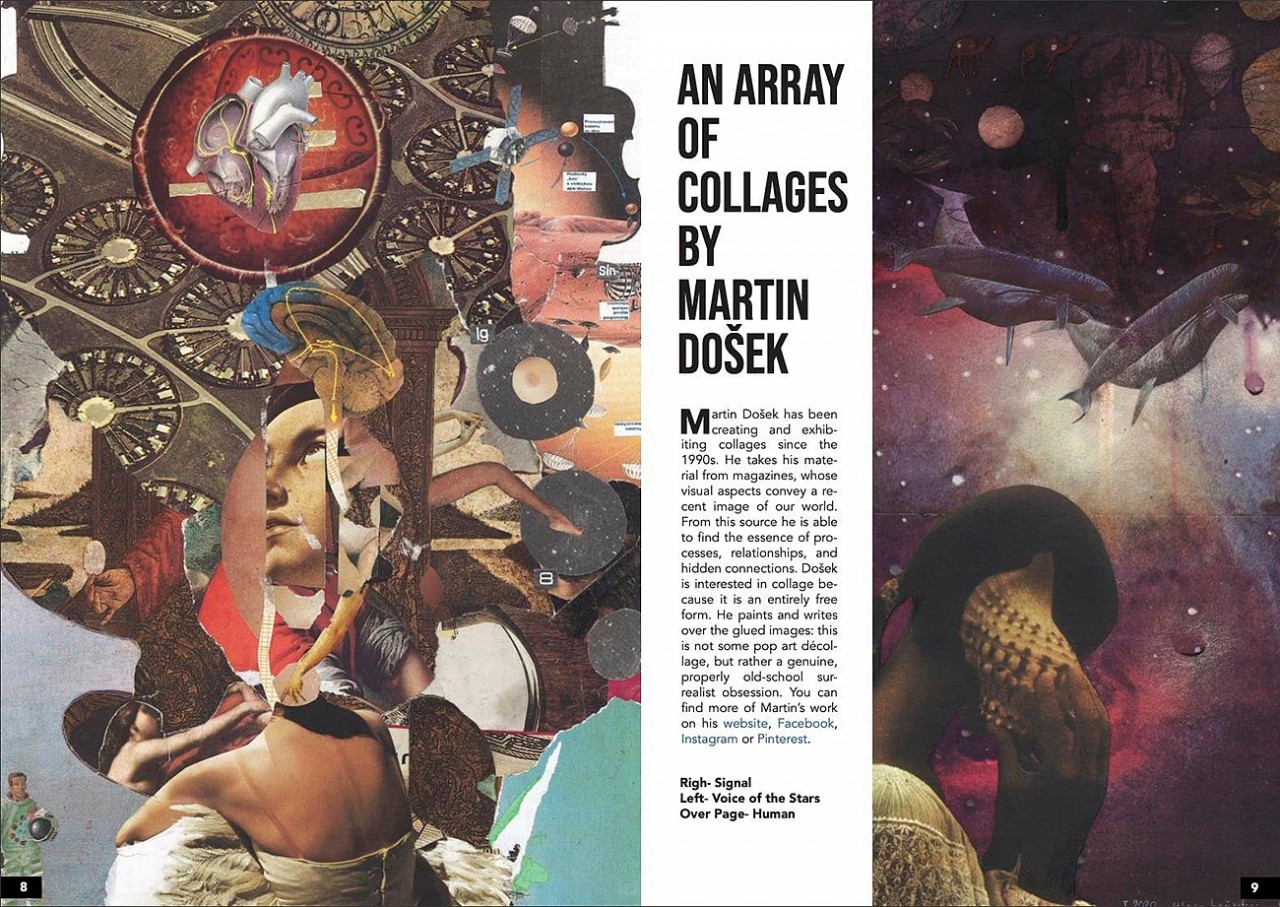

Collage was a favourite technique of the surrealist poets because it enabled them to immerse themselves in the same dream-like waters that the surrealist painters explored – without the need to do anything except cut, paste and let their imagination run free. Collage is a genuinely surrealist technique; it relies on the artist’s skill in stealing the original identity of the things they depict and then imbuing these things with a new identity – a much brighter identity, accompanied by a murderously sexy new story. The author of a collage can capture something phenomenal, something connected with secret dreams, eternal archetypes, lost knowledge: the artist knows the direction in which human imagery flows. Martin Došek has been creating and exhibiting collages since the 1990s. He takes his material from magazines, whose visual aspects convey a recent image of our world; in this source he is able to find the essence of processes, relationships, and hidden connections. He enters into famous images guided by a feeling of empathy – a form of Einfühlung – and above all in a spirit of fun.

His collages repeatedly feature a number of central themes. One of these is Salomé, the femme fatale so well-known from the art of the symbolists and film noir. The woman’s head in the background of the collage Sol is a sun, an explosion, a catastrophe and the cause of that catastrophe, a whimsical divine being. We are gladly transported to the vicinity of the stars, the very beginnings of the immense universe. The emergence of life and chaos theory are just as mysterious and inexplicable as human relationships or beauty. The collages lead us through dreams of paradise, of Utopia. We lose ourselves in an ocean alongside giant whales and nymphs. We accompany aviators on flights of discovery, pilgrims lost on their journeys to their destination and into the depths of their subconscious. We enter into the intimate preserve of sex and small pains. We are referred to films, overarching narratives of civilizations, and artistic masterpieces. The techniques are filmic: immersion, interaction, fragmentation, incompleteness, continuity, looping, hyper-reality…

Martin Došek’s collages from the 1990s are imbued with a dark atmosphere, their figures filling the entire available space. His later compositions are more fragmentary, with more striking colours. Each collage gives the impression of a cut from a music video, a film screened just once in time, or an exceptionally precise memory of a midnight dream. Došek is interested in collage because it is an entirely free form. He paints and writes over the glued images: this is not some pop art décollage, but rather a genuine, properly old-school surrealist obsession.

Martina Vítková, October 2019

---

I´m just playing, says Martin Došek with mysterious smile, which advises and bears to herewith his aversion to comment his production anyway. All the more he evokes the parallel with dutch painter, Hieronymus Bosch, who is indicated as a surrealist of the 15th century. Došek sticks his collages one by one with no less urgent memento, the same way as Bosch didn´t let anyone introspect into his inward, and disgorged pictures, presented the magic of the Middle Ages (with everything, what it meant), with crudeness, heading to the bone. Defile of women or girls on his collages, or more precisely their absolut adoration (pious veneration, not worship), with total absence of men (except of the holy ones), whose phallic presence is limited just to quizzical plumy creatures, evokes escapement into the false Eden, which has to lead along destruction of humankind. Surrealism is fortunately an avant-garde artistic direction, which has nothing in common with conventional logic schemes, and is plunging us in fantastic images and dreams. The power of Došek´s minimalist collages subsists in the fact, that we easily believe him, that Saint Sebastian was stabbed to the death by some courtesan during a ride in a limousine, or that a unicorn is a hairy blonde girl, indeed. The sins of the humankind have nowise fallen since the Middle Ages, vice versa maybe, the Last Judgment is still far from it. Maybe just a bizarre combination of dream and reality, life and death enables us to survive the unsurviveable.

Jarmila Kudláčková 2008, Translation: Kryštof Kudláček